- Home

- James Branch Cabell

The Cords of Vanity. A Comedy of Shirking

The Cords of Vanity. A Comedy of Shirking Read online

The Cords of Vanity. A Comedy of Shirking

James Branch Cabell

THE CORDS OF VANITY

A Comedy of Shirking

Revised and Expanded Edition

by JAMES BRANCH CABELL

with INTRODUCTION by WILSON FOLLETT

To

GABRIELLE BROOKE MONCURE

Plus sapit vulgus, quia tantum, quantum opus est, sapit.

AN INTRODUCTION

by Wilson Follett

Mr. Cabell, in making ready this second or intended edition of THE CORDS OF VANITY, performs an act of reclamation which is at the same time an act of fresh creation.

For the purely reclamatory aspect of what he has done, his reward (so far as that can consist in anything save the doing) must come from insignificantly few directions; so few indeed that he, with a wrily humorous exaggeration, affects to believe them singular. The author of this novel has been pleased to describe the author of this introduction as "the only known purchaser of the book" and, further, as "the other person to own a CORDS OF VANITY". I could readily enough acquit myself, with good sound legal proofs, of any such singularity as stands charged in this soft impeachment—and that without appeal to The Cleveland Plain Dealer of eleven years ago ("slushy and disgusting"), or to The New York Post ("sterile and malodorous … worse than immoral—dull"), or to Ainslee's Magazine ("inconsequent and rambling … rather nauseating at times"). These devotees of the adjective that hunts in pairs are hardly to be discussed, I suppose, in connection with any rewards except such as accrue to the possessors of a certain obtuseness, who always and infallibly reap at least the reward of not being hurt by what they do not know—or, for that matter, by what they do know. He who writes such a book as THE CORDS OF VANITY is committing himself to the supremely irrational faith that this dullness is somehow not the ultimate arbiter; and for him the pronouncements of this dullness simply do not figure among either his rewards or his penalties. So, it is not exactly to these tributes of the press that one reverts in noting that THE CORDS OF VANITY, on its publication eleven years ago, promptly became a book which there were—almost—none to praise and very few to love. After all, its author's computation of that former audience of his—his actual individual voluntary readers of a decade ago—appears to be but slightly and pardonably exaggerated on the more modest side of the fact. If there were a Cabell Club of membership determined solely by the number of those who, already possessing THE CORDS OF VANITY in its first edition, recognize it as the work of a serious artist of high achievement and higher capacity, I suspect that the smallness of that club would be in inordinate disproportion to everything but its selectness and its members' pride in "belonging".

Be that as it may, the economist-author, on the eve of his book's emergence from the limbo of "out of print", prefers that it come into its redemption carrying a foreword by someone who knew it without dislike in its former incarnation. No contingent liability, it seems, can dissuade Mr. Cabell from this preference. An author who once elected to precede a group of his best tales with an introduction eloquently setting forth reasons why the collection ought not to be published at all, is hardly to be deterred now by the mere inexpediency of hitching his star to a farm-wagon. His own graciously unreasonable insistence must be the excuse, such as it is, for the present introduction, such as it is. If there may be said to exist a sort of charter membership in Mr. Cabell's audience, this document is to be construed as representing its very enthusiastic welcome to the later and vastly larger elective membership.

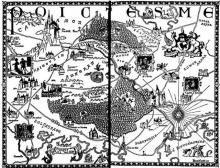

And if, weighed as such a welcome, it proves hopelessly inadequate, at least it provides a number of possible compensations by the way. For instance, that New York World critic who damned the book but praised its frontispiece of 1909, has now a uniquely pat opportunity to balance his ledger by praising the book and damning this foreword, which, more or less, replaces the frontispiece. Similarly, the more renowned critic and anthologist who so well knows the "originals" of the verses in From the Hidden Way, can now render poetically perfect justice to all who will care by perceiving that both the earlier edition of this book and the author of this foreword are but figments of Mr. Cabell's slightly puckish invention.

But these pages must not be, like those which follow, a comedy of shirking. They will have flouted a plain duty unless they speak of the sense and the degree in which this novel, during the process of reclaiming it, has been actually recreated. Perhaps the matter can be packed most succinctly into the statement that Mr. Cabell's hero has been subjected to such a process of growth as has made him commensurate in stature with the other two modern writers of Mr. Cabell's invention. As The Cream of the Jest is essentially the book of Felix Kennaston and Beyond Life that of John Charteris, so THE CORDS OF VANITY is essentially the book of Robert Etheridge Townsend. Now, this Townsend has accomplished a deal of growing since 1909. By this I do not mean that he is taken at a later period of his own imagined life, or that he fails to act consonantly with the extreme youth imputed to him: I mean that he is the creation of a more mature mind, a deeper philosophy, a more probing insight into the implications of things. A given youth of twenty-five will be very differently interpreted by an observer of thirty and by the same observer at forty, very much as a given era of the past will be understood differently by a single historian before and after certain cycles of his own social and political experience. The past never remains to us the same past; it grows up along with us; the physical facts may remain admittedly the same, but our understanding accents them differently, finds more in them at some points and less at others. So Robert Etheridge Townsend remains an example of that special temperament which, being unable to endure the contact of unhappiness, consistently shirks every responsibility that entails or threatens discomfort; and the truth about him, taking him as an example of just that temperament, is still inexorably told. But his weakness as a man becomes much more tolerable in this second version, because it is much more intimately and poignantly correlated with his strength as an artist. One is made to feel that he, like Charteris, may the better consummate in his art the auctorial virtues of distinction and clarity, beauty and symmetry, tenderness and truth and urbanity, precisely because his personal life is bereft of those virtues. Less than before, the accent is on the wastrel in Townsend; more than before, it is on the potential creator of beauty in him. The earlier readers will hardly count it as a fault that Mr. Cabell has contrived to make his novel, without detriment to any truth whatsoever, a far less unpleasant book. Sardonic it still is, by a necessary implication, but not wantonly, and with a mellowness. The irony, which at its harshest was capable of rasping the nerves, has become capable of wringing the heart.

Other reasons there are, too, for holding that THE CORDS OF VANITY is certain to make its second appeal to a many times multiplied audience. Since divers momentous transactions of the years just gone, the whole world stands in a moral position extraordinarily well adapted to the comprehension of just such a comedy of shirking; and especially the world of thought has received a powerful impulsion toward the area long occupied by Mr. Cabell's romantic pessimism. There is perhaps somewhat more demand for satire, or at least a growing toleration of it. Moreover, by sheer patience and reiteration Mr. Cabell has procured no little currency for some of his most characteristic ideas. Chivalry and gallantry, as he analyzes them, are concepts which play their part in the inevitable present re-editing of social and literary history. The Rivet in Grandfather's Neck, The Cream of the Jest, and The Certain Hour have somewhat to say to the discriminating, even on other than purely aesthetic grounds; Beyond Life is on the threshold of its day as the Sartor Resartus of one side, the aes

thetic side, of modernism;

"Of Jurgen eke they maken mencion";

and THE CORDS OF VANITY is but the first of the earlier books to be reissued in the format of the uniform and accessible Intended Edition.

While THE CORDS OF VANITY was out of print, a fresh copy is known to have been acquired for twenty-five cents. Copies of a more recent work by the same hand—a tale which has been rendered equally unavailable to the public, though by slightly different considerations—have fetched as much as one hundred times that sum. This arithmetic may be, in part, the gauge of an unsought and distasteful notoriety; but that very notoriety, by the most natural of transitions, will lead the curious on from what cannot be obtained to what can, and some who have begun by seeking one particular work of a great artist will end by discovering the artist. In short, it is rational to expect that the fortunes hereafter of this rewritten novel will very excellently illustrate the uses of adversity.

Not, I repeat, that any great part of the reward for such writing can come from without. According to Robert Etheridge Townsend, "a man writes admirable prose not at all for the sake of having it read, but for the more sensible reason that he enjoys playing solitaire"—a not un-Cabellian saying. And, even of the reward from without, it may be questioned whether the really indispensable part ever comes from the multitude. A lady with whose more candid opinions the writer of this is more frequently favored nowadays than of old has said: "Every time I hear of somebody who has wanted one of these books without being able to get it, or who, having got it, has conceded it nothing better than the disdain of an ignoramus, I feel as if I must forthwith get out the copy and read it through again and again, until I have read it once for every person who has rejected it or been denied it." One may feel reasonably sure that it is this kind of solicitude, rather than any possible sanction from the crowd, which would be thought of by the author of this book as "the exact high prize through desire of which we write".

WILSON FOLLETT.

CHESHIRE, CONNECTICUT

May, 1920

The Prologue: Which Deals with the Essentials

"In the house and garden of his dream he saw a child moving, and could divide the main streams at least of the winds that had played on him, and study so the first stage in that mental journey."

1—Writing

It appeared to me that my circumstances clamored for betterment, because never in my life have I been able to endure the contact of unhappiness. And my mother was always crying now, over (though I did not know it) the luckiest chance which had ever befallen her; and that made me cry too, without understanding exactly why.

So the child, that then was I, procured a pencil and a bit of wrapping-paper, and began to write laboriously:

"DEAR LORD

"You know that Papa died and please comfort Mama and give Father a crown of Glory Ammen

"Your lamb and very sincerely yours

"ROBERT ETHERIDGE TOWNSEND."

This appeared to the point as I re-read it, and of course God would understand that children were not expected to write quite as straight across the paper as grown people. The one problem was how to deliver this, my first letter, most expeditiously, because when your mother cried you always cried too, and couldn't stop, not even when you wanted to, not even when she promised you five cents, and it all made you horribly uncomfortable.

I knew that the big Bible on the parlor table was God's book. Probably God read it very often, since anybody would be proud of having written a book as big as that and would want to look at it every day. So I tiptoed into the darkened parlor. I use the word advisedly, for there was not at this period any drawing-room in Lichfield, and besides, a drawing-room is an entirely different matter.

Everywhere the room was cool, and, since the shades were down, the outlines of the room's contents were uncomfortably dubious; for just where the table stood had been, five days ago, a big and oddly-shaped black box with beautiful silver handles; and Uncle George had lifted me so that I could see through the pane of glass, which was a part of this funny box, while an infinity of decorous people rustled and whispered….

I remember knowing they were "company" and thinking they coughed and sniffed because they were sorry that my father was dead. In the light of knowledge latterly acquired, I attribute these actions to the then prevalent weather, for even now I recall how stiflingly the room smelt of flowers—particularly of magnolia blossoms—and of rubber and of wet umbrellas. For my own part, I was not at all sorry, though of course I pretended to be, since I had always known that as a rule my father whipped me because he had just quarreled with my mother, and that he then enjoyed whipping me.

I desired, in fine, that he should stay dead and possess his crown of glory in Heaven, which was reassuringly remote, and that my mother should stop crying. So I slipped my note into the Apocrypha….

I felt that somewhere in the room was God and that God was watching me, but I was not afraid. Yet I entertained, in common with most children, a nebulous distrust of this mysterious Person, a distrust of which I was particularly conscious on winter nights when the gas had been turned down to a blue fleck, and the shadow of the mantelpiece flickered and plunged on the ceiling, and the clock ticked louder and louder, in prediction (I suspected) of some terrible event very close at hand.

Then you remembered such unpleasant matters as Elisha and his bears, and those poor Egyptian children who had never even spoken to Moses, and that uncomfortably abstemious lady, in the fat blue-covered Arabian Nights, who ate nothing but rice, grain by grain—in the daytime…. And you called Mammy, and said you were very thirsty and wanted a glass of water, please.

To-day, though, while acutely conscious of that awful inspection, and painstakingly careful not to look behind me, I was not, after all, precisely afraid. If God were a bit like other people I knew He would say, "What an odd child!" and I liked to have people say that. Still, there was sunlight in the hall, and lots of sunlight, not just long and dusty shreds of sunlight, and I felt more comfortable when I was back in the hall.

2—Reading

I lay flat upon my stomach, having found that posture most conformable to the practice of reading, and I considered the cover of this slim, green book; the name of John Charteris, stamped thereon in fat-bellied letters of gold, meant less to me than it was destined to signify thereafter.

A deal of puzzling matter I found in this book, but in my memory, always, one fantastic passage clung as a burr to sheep's wool. That fable, too, meant less to me than it was destined to signify thereafter, when the author of it was used to declare that he had, unwittingly, written it about me. Then I read again this

Fable of the Foolish Prince

"As to all earlier happenings I choose in this place to be silent. Anterior adventures he had known of the right princely sort. But concerning his traffic with Schamir, the chief talisman, and how through its aid he won to the Sun's Sister for a little while; and concerning his dealings with the handsome Troll-wife (in which affair the cat he bribed with butter and the elm-tree he had decked with ribbons helped him); and with that beautiful and dire Thuringian woman whose soul was a red mouse: we have in this place naught to do. Besides, the Foolish Prince had put aside such commerce when the Fairy came to guide him; so he, at least, could not in equity have grudged the same privilege to his historian.

"Thus, the Fairy leading, the Foolish Prince went skipping along his father's highway. But the road was bordered by so many wonders—as here a bright pebble and there an anemone, say, and, just beyond, a brook which babbled an entreaty to be tasted,—that many folk had presently overtaken and had passed the loitering Foolish Prince. First came a grandee, supine in his gilded coach, with half-shut eyes, uneagerly meditant upon yesterday's statecraft or to-morrow's gallantry; and now three yokels, with ruddy cheeks and much dust upon their shoulders; now a haggard man in black, who constantly glanced backward; and now a corporal with an empty sleeve, who whistled as he went.

"A butterfly guided ev

ery man of them along the highway. 'For the Lord of the Fields is a whimsical person,' said the Fairy,' and such is his very old enactment concerning the passage even of his cowpath; but princes each in his day and in his way may trample this domain as prompt their will and skill.'

"'That now is excellent hearing,' said the Foolish Prince; and he strutted.

"'Look you,' said the Fairy, 'a man does not often stumble and break his shins in the highway, but rather in the byway.'….

"Thus, the Fairy leading, the Foolish Prince went skipping on his allotted journey, though he paused once in a while to shake his bauble at the staring sun.

"'The stars,' he considered, 'are more sympathetic….

"And thus, the Fairy leading, they came at last to a tall hedge wherein were a hundred wickets, all being closed; and those who had passed the Foolish Prince disputed before the hedge and measured the hundred wickets with thirty-nine articles and with a variety of instruments, and each man entered at his chosen wicket, and a butterfly went before him; but no man returned into the open country.

"'Now beyond each wicket,' said the Fairy, 'lies a great crucible, and by ninety and nine of these crucibles is a man consumed, or else transmuted into this animal or that animal. For such is the law in these parts and in human hearts.'

"The Prince demanded how if one found by chance the hundredth wicket? But she shook her head and said that none of the Tylwydd Teg was permitted to enter the Disenchanted Garden. Rumor had it that within the Garden, beyond the crucibles, was a Tree, but whether the fruit of this Tree were sweet or bitter no person in the Fields could tell, nor did the Fairy pretend to know what happened in the Garden.

Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice

Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice Chivalry

Chivalry Figures of Earth: A Comedy of Appearances

Figures of Earth: A Comedy of Appearances_preview.jpg) The Certain Hour (Dizain des Poëtes)

The Certain Hour (Dizain des Poëtes) Domnei: A Comedy of Woman-Worship

Domnei: A Comedy of Woman-Worship The Line of Love; Dizain des Mariages

The Line of Love; Dizain des Mariages The Line of Love. Dizain des Mariages

The Line of Love. Dizain des Mariages The Certain Hour. Dizain des Poëtes

The Certain Hour. Dizain des Poëtes The Jewel Merchants. A Comedy in One Act

The Jewel Merchants. A Comedy in One Act Gallantry. Dizain des Fetes Galantes

Gallantry. Dizain des Fetes Galantes The Cords of Vanity. A Comedy of Shirking

The Cords of Vanity. A Comedy of Shirking Domnei. A Comedy of Woman-Worship

Domnei. A Comedy of Woman-Worship Figures of Earth

Figures of Earth Jurgen. A Comedy of Justice

Jurgen. A Comedy of Justice Taboo. A Legend Retold from the Dirghic of Sævius Nicanor, with Prolegomena, Notes, and a Preliminary Memoir

Taboo. A Legend Retold from the Dirghic of Sævius Nicanor, with Prolegomena, Notes, and a Preliminary Memoir