- Home

Page 3

Page 3

Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice

Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice Chivalry

Chivalry Figures of Earth: A Comedy of Appearances

Figures of Earth: A Comedy of Appearances_preview.jpg) The Certain Hour (Dizain des Poëtes)

The Certain Hour (Dizain des Poëtes) Domnei: A Comedy of Woman-Worship

Domnei: A Comedy of Woman-Worship The Line of Love; Dizain des Mariages

The Line of Love; Dizain des Mariages The Line of Love. Dizain des Mariages

The Line of Love. Dizain des Mariages The Certain Hour. Dizain des Poëtes

The Certain Hour. Dizain des Poëtes The Jewel Merchants. A Comedy in One Act

The Jewel Merchants. A Comedy in One Act Gallantry. Dizain des Fetes Galantes

Gallantry. Dizain des Fetes Galantes The Cords of Vanity. A Comedy of Shirking

The Cords of Vanity. A Comedy of Shirking Domnei. A Comedy of Woman-Worship

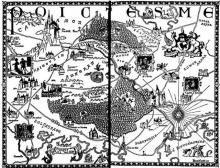

Domnei. A Comedy of Woman-Worship Figures of Earth

Figures of Earth Jurgen. A Comedy of Justice

Jurgen. A Comedy of Justice Taboo. A Legend Retold from the Dirghic of Sævius Nicanor, with Prolegomena, Notes, and a Preliminary Memoir

Taboo. A Legend Retold from the Dirghic of Sævius Nicanor, with Prolegomena, Notes, and a Preliminary Memoir