- Home

- James Branch Cabell

The Line of Love; Dizain des Mariages Page 4

The Line of Love; Dizain des Mariages Read online

Page 4

CHAPTER I

_The Episode Called The Wedding Jest_

1. _Concerning Several Compacts_

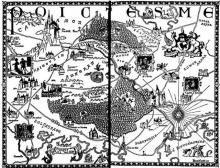

It is a tale which they narrate in Poictesme, telling how love beganbetween Florian de Puysange and Adelaide de la Foret. They tell also howyoung Florian had earlier fancied other women for one reason or another;but that this, he knew, was the great love of his life, and a love whichwould endure unchanged as long as his life lasted.

And the tale tells how the Comte de la Foret stroked a gray beard, andsaid, "Well, after all, Puysange is a good fief--"

"As if that mattered!" cried his daughter, indignantly. "My father, youare a deplorably sordid person."

"My dear," replied the old gentleman, "it does matter. Fiefs last."

So he gave his consent to the match, and the two young people weremarried on Walburga's Eve, on the day that ends April.

And they narrate how Florian de Puysange was vexed by a thought that wasin his mind. He did not know what this thought was. But something he hadoverlooked; something there was he had meant to do, and had not done: anda troubling consciousness of this lurked at the back of his mind like asmall formless cloud. All day, while bustling about other matters, he hadgroped toward this unapprehended thought.

Now he had it: Tiburce.

The young Vicomte de Puysange stood in the doorway, looking back into thebright hall where they of Storisende were dancing at his marriage feast.His wife, for a whole half-hour his wife, was dancing with handsomeEtienne de Nerac. Her glance met Florian's, and Adelaide flashed him anespecial smile. Her hand went out as though to touch him, for all thatthe width of the hall severed them.

Florian remembered presently to smile back at her. Then he went out ofthe castle into a starless night that was as quiet as an unvoiced menace.A small and hard and gnarled-looking moon ruled over the dusk's secrecy.The moon this night, afloat in a luminous gray void, somehow remindedFlorian of a glistening and unripe huge apple.

The foliage about him moved at most as a sleeper breathes, while Floriandescended eastward through walled gardens, and so came to the graveyard.White mists were rising, such mists as the witches of Amnerannotoriously evoked in these parts on each Walburga's Eve to purchaserecreations which squeamishness leaves undescribed.

For five years now Tiburce d'Arnaye had lain there. Florian thought ofhis dead comrade and of the love which had been between them--a love moreperfect and deeper and higher than commonly exists between men--and thethought came to Florian, and was petulantly thrust away, that Adelaideloved ignorantly where Tiburce d'Arnaye had loved with comprehension.Yes, he had known almost the worst of Florian de Puysange, this dear ladwho, none the less, had flung himself between Black Torrismond's swordand the breast of Florian de Puysange. And it seemed to Florian unfairthat all should prosper with him, and Tiburce lie there imprisoned indirt which shut away the color and variousness of things and thedrollness of things, wherein Tiburce d'Arnaye had taken such joy. AndTiburce, it seemed to Florian--for this was a strange night--wasstruggling futilely under all that dirt, which shut out movement, andclogged the mouth of Tiburce, and would not let him speak; and wasstruggling to voice a desire which was unsatisfied and hopeless.

"O comrade dear," said Florian, "you who loved merriment, there is afeast afoot on this strange night, and my heart is sad that you are nothere to share in the feasting. Come, come, Tiburce, a right trustyfriend you were to me; and, living or dead, you should not fail to makemerry at my wedding."

Thus he spoke. White mists were rising, and it was Walburga's Eve.

So a queer thing happened, and it was that the earth upon the gravebegan to heave and to break in fissures, as when a mole passes throughthe ground. And other queer things happened after that, and presentlyTiburce d'Arnaye was standing there, gray and vague in the moonlight ashe stood there brushing the mold from his brows, and as he stood thereblinking bright wild eyes. And he was not greatly changed, it seemed toFlorian; only the brows and nose of Tiburce cast no shadows upon hisface, nor did his moving hand cast any shadow there, either, though themoon was naked overhead.

"You had forgotten the promise that was between us," said Tiburce; andhis voice had not changed much, though it was smaller.

"It is true. I had forgotten. I remember now." And Florian shivered alittle, not with fear, but with distaste.

"A man prefers to forget these things when he marries. It is naturalenough. But are you not afraid of me who come from yonder?"

"Why should I be afraid of you, Tiburce, who gave your life for mine?"

"I do not say. But we change yonder."

"And does love change, Tiburce? For surely love is immortal."

"Living or dead, love changes. I do not say love dies in us who may hopeto gain nothing more from love. Still, lying alone in the dark clay,there is nothing to do, as yet, save to think of what life was, and ofwhat sunlight was, and of what we sang and whispered in dark places whenwe had lips; and of how young grass and murmuring waters and the highstars beget fine follies even now; and to think of how merry our lovedones still contrive to be, even now, with their new playfellows. Suchreflections are not always conducive to philanthropy."

"Tell me," said Florian then, "and is there no way in which we who arestill alive may aid you to be happier yonder?"

"Oh, but assuredly," replied Tiburce d'Arnaye, and he discoursed ofcurious matters; and as he talked, the mists about the graveyardthickened. "And so," Tiburce said, in concluding his tale, "it is notpermitted that I make merry at your wedding after the fashion of thosewho are still in the warm flesh. But now that you recall our ancientcompact, it is permitted I have my peculiar share in the merriment, and Imay drink with you to the bride's welfare."

"I drink," said Florian, as he took the proffered cup, "to the welfare ofmy beloved Adelaide, whom alone of women I have really loved, and whom Ishall love always."

"I perceive," replied the other, "that you must still be having yourjoke."

Then Florian drank, and after him Tiburce. And Florian said, "But it is astrange drink, Tiburce, and now that you have tasted it you are changed."

"You have not changed, at least," Tiburce answered; and for the firsttime he smiled, a little perturbingly by reason of the change in him.

"Tell me," said Florian, "of how you fare yonder."

So Tiburce told him of yet more curious matters. Now the augmenting mistshad shut off all the rest of the world. Florian could see only vaguerolling graynesses and a gray and changed Tiburce sitting there, withbright wild eyes, and discoursing in a small chill voice. The appearanceof a woman came, and sat beside him on the right. She, too, was gray, asbecame Eve's senior: and she made a sign which Florian remembered, and ittroubled him.

Tiburce said then, "And now, young Florian, you who were once so dear tome, it is to your welfare I drink."

"I drink to yours, Tiburce."

Tiburce drank first: and Florian, having drunk in turn, cried out, "Youhave changed beyond recognition!"

"You have not changed," Tiburce d'Arnaye replied again. "Now let me tellyou of our pastimes yonder."

With that he talked of exceedingly curious matters. And Florian began togrow dissatisfied, for Tiburce was no longer recognizable, and Tiburcewhispered things uncomfortable to believe; and other eyes, as wild ashis, but lit with red flarings from behind, like a beast's eyes, showedin the mists to this side and to that side, for unhappy beings werepassing through the mists upon secret errands which they dischargedunwillingly. Then, too, the appearance of a gray man now sat to the leftof that which had been Tiburce d'Arnaye, and this newcomer was marked sothat all might know who he was: and Florian's heart was troubled to notehow handsome and how admirable was that desecrated face even now.

"But I must go," said Florian, "lest they miss me at Storisende, andAdelaide be worried."

"Surely it will not take long to toss off a third cup. Nay, comrade, whowere once so dear, let us two now drink our last toast together. Then go,in Sclaug's name, and celebrate

your marriage. But before that let usdrink to the continuance of human mirth-making everywhere."

Florian drank first. Then Tiburce took his turn, looking at Florian asTiburce drank slowly. As he drank, Tiburce d'Arnaye was changed evenmore, and the shape of him altered, and the shape of him trickled asthough Tiburce were builded of sliding fine white sand. So Tiburced'Arnaye returned to his own place. The appearances that had sat to hisleft and to his right were no longer there to trouble Florian withmemories. And Florian saw that the mists of Walburga's Eve had departed,and that the sun was rising, and that the graveyard was all overgrownwith nettles and tall grass.

He had not remembered the place being thus, and it seemed to him thenight had passed with unnatural quickness. But he thought more of thefact that he had been beguiled into spending his wedding-night in agraveyard, in such questionable company, and of what explanation he couldmake to Adelaide.

2. _Of Young Persons in May_

The tale tells how Florian de Puysange came in the dawn through floweringgardens, and heard young people from afar, already about their maying.Two by two he saw them from afar as they went with romping and laughterinto the tall woods behind Storisende to fetch back the May-pole withdubious old rites. And as they went they sang, as was customary, thatsong which Raimbaut de Vaqueiras made in the ancient time in honor ofMay's ageless triumph.

Sang they:

"_May shows with godlike showing To-day for each that sees May's magic overthrowing All musty memories In him whom May decrees To be love's own. He saith, 'I wear love's liveries Until released by death_.'

"_Thus all we laud May's sowing, Nor heed how harvests please When nowhere grain worth growing Greets autumn's questing breeze, And garnerers garner these-- Vain words and wasted breath And spilth and tasteless lees-- Until released by death._

"_Unwillingly foreknowing That love with May-time flees, We take this day's bestowing, And feed on fantasies Such as love lends for ease Where none but travaileth, With lean infrequent fees, Until released by death_."

And Florian shook his sleek black head. "A very foolish and pessimisticalold song, a superfluous song, and a song that is particularly out ofplace in the loveliest spot in the loveliest of all possible worlds."

Yet Florian took no inventory of the gardens. There was but a happy senseof green and gold, with blue topping all; of twinkling, fluent, tossingleaves and of the gray under side of elongated, straining leaves; a senseof pert bird noises, and of a longer shadow than usual slanting beforehim, and a sense of youth and well-being everywhere. Certainly it wasnot a morning wherein pessimism might hope to flourish.

Instead, it was of Adelaide that Florian thought: of the tall, impulsive,and yet timid, fair girl who was both shrewd and innocent, and of hertenderly colored loveliness, and of his abysmally unmerited felicity inhaving won her. Why, but what, he reflected, grimacing--what if he hadtoo hastily married somebody else? For he had earlier fancied other womenfor one reason or another: but this, he knew, was the great love of hislife, and a love which would endure unchanged as long as his life lasted.

3. _What Comes of Marrying Happily_

The tale tells how Florian de Puysange found Adelaide in the company oftwo ladies who were unknown to him. One of these was very old, the otheran imposing matron in middle life. The three were pleasantly shaded byyoung oak-trees; beyond was a tall hedge of clipped yew. The older womenwere at chess, while Adelaide bent her meek golden head to some of thatfine needlework in which the girl delighted. And beside them rippled asmall sunlit stream, which babbled and gurgled with silver flashes.Florian hastily noted these things as he ran laughing to his wife.

"Heart's dearest--!" he cried. And he saw, perplexed, that Adelaide hadrisen with a faint wordless cry, and was gazing at him as though shewere puzzled and alarmed a very little.

"Such an adventure as I have to tell you of!" says Florian then.

"But, hey, young man, who are you that would seem to know my daughter sowell?" demands the lady in middle life, and she rose majestically fromher chess-game.

Florian stared, as he well might. "Your daughter, madame! But certainlyyou are not Dame Melicent."

At this the old, old woman raised her nodding head. "Dame Melicent? Andwas it I you were seeking, sir?"

Now Florian looked from one to the other of these incomprehensiblestrangers, bewildered: and his eyes came back to his lovely wife, and hislips smiled irresolutely. "Is this some jest to punish me, my dear?"

But then a new and graver trouble kindled in his face, and his eyesnarrowed, for there was something odd about his wife also.

"I have been drinking in queer company," he said. "It must be that myhead is not yet clear. Now certainly it seems to me that you are Adelaidede la Foret, and certainly it seems to me that you are not Adelaide."

The girl replied, "Why, no, messire; I am Sylvie de Nointel."

"Come, come," says the middle-aged lady, briskly, "let us make an end tothis play-acting, and, young fellow, let us have a sniff at you. No, youare not tipsy, after all. Well, I am glad of that. So let us get to thebottom of this business. What do they call you when you are at home?"

"Florian de Puysange," he answered, speaking meekly enough. This capablelarge person was to the young man rather intimidating.

"La!" said she. She looked at him very hard. She nodded gravely two orthree times, so that her double chin opened and shut. "Yes, and you favorhim. How old are you?"

He told her twenty-four.

She said, inconsequently: "So I was a fool, after all. Well, young man,you will never be as good-looking as your father, but I trust you have anhonester nature. However, bygones are bygones. Is the old rascal stillliving? and was it he that had the impudence to send you to me?"

"My father, madame, was slain at the battle of Marchfeld--"

"Some fifty years ago! And you are twenty-four. Young man, yourparentage had unusual features, or else we are at cross-purposes. Let usstart at the beginning of this. You tell us you are called Florian dePuysange and that you have been drinking in queer company. Now let ushave the whole story."

Florian told of last night's happenings, with no more omissions thanseemed desirable with feminine auditors.

Then the old woman said: "I think this is a true tale, my daughter, forthe witches of Amneran contrive strange things, with mists to aid them,and with Lilith and Sclaug to abet. Yes, and this fate has fallen beforeto men that were over-friendly with the dead."

"Stuff and nonsense!" said the stout lady.

"But, no, my daughter. Thus seven persons slept at Ephesus, from the timeof Decius to the time of Theodosius--"

"Still, Mother--"

"--And the proof of it is that they were called Constantine and Dionysiusand John and Malchus and Marcian and Maximian and Serapion. They wereduly canonized. You cannot deny that this thing happened withoutasserting no less than seven blessed saints to have been unprincipledliars, and that would be a very horrible heresy--"

"Yet, Mother, you know as well as I do--"

"--And thus Epimenides, another excellently spoken-of saint, slept atAthens for fifty-seven years. Thus Charlemagne slept in the Untersberg,and will sleep until the ravens of Miramon Lluagor have left hismountains. Thus Rhyming Thomas in the Eildon Hills, thus Ogier in Avalon,thus Oisin--"

The old lady bade fair to go on interminably in her gentle resolutepiping old voice, but the other interrupted.

"Well, Mother, do not excite yourself about it, for it only makes yourasthma worse, and does no especial good to anybody. Things may be as yousay. Certainly I intended nothing irreligious. Yet these extended naps,appropriate enough for saints and emperors, are out of place in one's ownfamily. So, if it is not stuff and nonsense, it ought to be. And that Istick to."

"But we forget the boy, my dear," said the old lady. "Now listen, Floriande Puysange. Thirty years ago last night, to the month and the day, itwas that you vanished from our knowledge, leaving my daughter a forsakenbride. For I am what t

he years have made of Dame Melicent, and this is mydaughter Adelaide, and yonder is her daughter Sylvie de Nointel."

"La, Mother," observed the stout lady, "but are you certain it was thelast of April? I had been thinking it was some time in June. And Iprotest it could not have been all of thirty years. Let me see now,Sylvie, how old is your brother Richard? Twenty-eight, you say. Well,Mother, I always said you had a marvelous memory for things like that,and I often envy you. But how time does fly, to be sure!"

And Florian was perturbed. "For this is an awkward thing, and Tiburce hasplayed me an unworthy trick. He never did know when to leave off joking;but such posthumous frivolity is past endurance. For, see now, in what apickle it has landed me! I have outlived my friends, I may encounterdifficulty in regaining my fiefs, and certainly I have lost the fairestwife man ever had. Oh, can it be, madame, that you are indeed myAdelaide!"

"Yes, every pound of me, poor boy, and that says much."

"--And that you have been untrue to the eternal fidelity which you vowedto me here by this very stream! Oh, but I cannot believe it was thirtyyears ago, for not a grass-blade or a pebble has been altered; and Iperfectly remember the lapping of water under those lichened rocks, andthat continuous file of ripples yonder, which are shaped likearrowheads."

Adelaide rubbed her nose. "Did I promise eternal fidelity? I can hardlyremember that far back. But I remember I wept a great deal, and myparents assured me you were either dead or a rascal, so that tears couldnot help either way. Then Ralph de Nointel came along, good man, and mademe a fair husband, as husbands go--"

"As for that stream," then said Dame Melicent, "it is often I havethought of that stream, sitting here with my grandchildren where I oncesat with gay young men whom nobody remembers now save me. Yes, it isstrange to think that instantly, and within the speaking of any simpleword, no drop of water retains the place it had before the word wasspoken: and yet the stream remains unchanged, and stays as it was when Isat here with those young men who are gone. Yes, that is a strangethought, and it is a sad thought, too, for those of us who are old."

"But, Mother, of course the stream remains unchanged," agreed DameAdelaide. "Streams always do except after heavy rains. Everybody knowsthat, and I can see nothing very remarkable about it. As for you,Florian, if you stickle for love's being an immortal affair," she added,with a large twinkle, "I would have you know I have been a widow forthree years. So the matter could be arranged."

Florian looked at her sadly. To him the situation was incongruous withthe terrible archness of a fat woman. "But, madame, you are no longer thesame person."

She patted him upon the shoulder. "Come, Florian, there is some sense inyou, after all. Console yourself, lad, with the reflection that if youhad stuck manfully by your wife instead of mooning about graveyards, Iwould still be just as I am to-day, and you would be tied to me. Yourfriend probably knew what he was about when he drank to our welfare, forwe would never have suited each other, as you can see for yourself. Well,Mother, many things fall out queerly in this world, but with age we learnto accept what happens without flustering too much over it. What are weto do with this resurrected old lover of mine?"

It was horrible to Florian to see how prosaically these women dealt withhis unusual misadventure. Here was a miracle occurring virtually beforetheir eyes, and these women accepted it with maddening tranquillity as anaffair for which they were not responsible. Florian began to reflect thatelderly persons were always more or less unsympathetic and inadequate.

"First of all," says Dame Melicent, "I would give him some breakfast. Hemust be hungry after all these years. And you could put him inAdhelmar's room--"

"But," Florian said wildly, to Dame Adelaide, "you have committed thecrime of bigamy, and you are, after all, my wife!"

She replied, herself not untroubled: "Yes, but, Mother, both the cook andthe butler are somewhere in the bushes yonder, up to some nonsense that Iprefer to know nothing about. You know how servants are, particularly onholidays. I could scramble him some eggs, though, with a rasher. AndAdhelmar's room it had better be, I suppose, though I had meant to haveit turned out. But as for bigamy and being your wife," she concluded morecheerfully, "it seems to me the least said the soonest mended. It is tonobody's interest to rake up those foolish bygones, so far as I can see."

"Adelaide, you profane equally love, which is divine, and marriage, whichis a holy sacrament."

"Florian, do you really love Adelaide de Nointel?" asked this terriblewoman. "And now that I am free to listen to your proposals, do you wishto marry me?"

"Well, no," said Florian: "for, as I have just said; you are no longerthe same person."

"Why, then, you see for yourself. So do you quit talking nonsense aboutimmortality and sacraments."

"But, still," cried Florian, "love is immortal. Yes, I repeat to you,precisely as I told Tiburce, love is immortal."

Then says Dame Melicent, nodding her shriveled old head: "When I wasyoung, and was served by nimbler senses and desires, and was housed inbrightly colored flesh, there were a host of men to love me. Minstrelsyet tell of the men that loved me, and of how many tall men were slainbecause of their love for me, and of how in the end it was Perion who wonme. For the noblest and the most faithful of all my lovers was Perion ofthe Forest, and through tempestuous years he sought me with a love thatconquered time and chance: and so he won me. Thereafter he made me a fairhusband, as husbands go. But I might not stay the girl he had loved, normight he remain the lad that Melicent had dreamed of, with dreamsbe-drugging the long years in which Demetrios held Melicent a prisoner,and youth went away from her. No, Perion and I could not do that, anymore than might two drops of water there retain their place in thestream's flowing. So Perion and I grew old together, friendly enough;and our senses and desires began to serve us more drowsily, so that wedid not greatly mind the falling away of youth, nor greatly mind to notewhat shriveled hands now moved before us, performing common tasks; and wewere content enough. But of the high passion that had wedded us there wasno trace, and of little senseless human bickerings there were a greatmany. For one thing"--and the old lady's voice was changed--"for onething, he was foolishly particular about what he would eat and what hewould not eat, and that upset my housekeeping, and I had never anypatience with such nonsense."

"Well, none the less," said Florian, "it is not quite nice of you toacknowledge it."

Then said Dame Adelaide: "That is a true word, Mother. All men getfinicky about their food, and think they are the only persons to beconsidered, and there is no end to it if once you begin to humor them. Sothere has to be a stand made. Well, and indeed my poor Ralph, too, wasall for kissing and pretty talk at first, and I accepted it willinglyenough. You know how girls are. They like to be made much of, and it isperfectly natural. But that leads to children. And when the childrenbegan to come, I had not much time to bother with him: and Ralph had hisfarming and his warfaring to keep him busy. A man with a growing familycannot afford to neglect his affairs. And certainly, being no fool, hebegan to notice that girls here and there had brighter eyes and trimmerwaists than I. I do not know what such observations may have led to whenhe was away from me: I never inquired into it, because in such mattersall men are fools. But I put up with no nonsense at home, and he made mea fair husband, as husbands go. That much I will say for him gladly: andif any widow says more than that, Florian, do you beware of her, for sheis an untruthful woman."

"Be that as it may," replied Florian, "it is not quite becoming to speakthus of your dead husband. No doubt you speak the truth: there is notelling what sort of person you may have married in what still seems tome unseemly haste to provide me with a successor: but even so, a littlecharitable prevarication would be far more edifying."

He spoke with such earnestness that there fell a silence. The womenseemed to pity him. And in the silence Florian heard from afar youngpersons returning from the woods behind Storisende, and bringing withthem the May-pole. They were still singing.

S

ang they:

"_Unwillingly foreknowing That love with May-time flees, We take this day's bestowing, And feed on fantasies_--"

4. _Youth Solves It_

The tale tells how lightly and sweetly, and compassionately, too, thenspoke young Sylvie de Nointel.

"Ah, but, assuredly, Messire Florian, you do not argue with my petsquite seriously! Old people always have some such queer notions. Ofcourse love all depends upon what sort of person you are. Now, as I seeit, Mama and Grandmama are not the sort of persons who have reallove-affairs. Devoted as I am to both of them, I cannot but perceive theyare lacking in real depth of sentiment. They simply do not understand orcare about such matters. They are fine, straightforward, practicalpersons, poor dears, and always have been, of course, for in things likethat one does not change, as I have often noticed. And Father, andGrandfather Perion, too, as I remember him, was kind-hearted andadmirable and all that, but nobody could ever have expected him to be asatisfactory lover. Why, he was bald as an egg, the poor pet!"

And Sylvie laughed again at the preposterous notions of old people. Sheflashed an especial smile at Florian. Her hand went out as though totouch him, in an unforgotten gesture. "Old people do not understand,"said Sylvie de Nointel, in tones which took this handsome young fellowineffably into confidence.

"Mademoiselle," said Florian, with a sigh that was part relief and allapproval, "it is you who speak the truth, and your elders have fallenvictims to the cynicism of a crassly material age. Love is immortal whenit is really love and when one is the right sort of person. There is thelove--known to how few, alas! and a passion of which I regret to findyour mother incapable--that endures unchanged until the end of life."

"I am so glad you think so, Messire Florian," she answered demurely.

"And do you not think so, mademoiselle?"

"How should I know," she asked him, "as yet?" He noted she had incrediblylong lashes.

"Thrice happy is he that convinces you!" says Florian. And about them,who were young in the world's recaptured youth, spring triumphed with anageless rural pageant, and birds cried to their mates. He noted the redbrevity of her lips and their probable softness.

Meanwhile the elder women regarded each other.

"It is the season of May. They are young and they are together. Poorchildren!" said Dame Melicent. "Youth cries to youth for the toys ofyouth, and saying, 'Lo, I cry with the voice of a great god!'"

"Still," said Madame Adelaide, "Puysange is a good fief--"

But Florian heeded neither of them as he stood there by the sunlitstream, in which no drop of water retained its place for a moment, andwhich yet did not alter in appearance at all. He did not heed his eldersfor the excellent reason that Sylvie de Nointel was about to speak, andhe preferred to listen to her. For this girl, he knew, was lovelier thanany other person had ever been since Eve first raised just such admiring,innocent, and venturesome eyes to inspect what must have seemed to herthe quaintest of all animals, called man. So it was with a shrug thatFlorian remembered how he had earlier fancied other women for one reasonor another; since this, he knew, was the great love of his life, and alove which would endure unchanged as long as his life lasted.

* * * * *

APRIL 14, 1355--OCTOBER 23, 1356

"_D'aquest segle flac, plen de marrimen,S'amor s'en vai, son jot teinh mensongier_."

_So Florian married Sylvie, and made her, they relate, a fair husband,as husbands go. And children came to them, and then old age, and, lastly,that which comes to all._

Which reminds me that it was an uncomfortable number of years ago, in anout-of-the-way corner of the library at Allonby Shaw, that I first cameupon_ Les Aventures d'Adhelmar de Nointel. _This manuscript dates fromthe early part of the fifteenth century and is attributed--though on novery conclusive evidence, says Hinsauf,--to the facile pen of Nicolas deCaen (circa 1450), until lately better known as a lyric poet andsatirist._

_The story, told in decasyllabic couplets, interspersed after a ratherunusual fashion with innumerable lyrics, seems in the main authentic. SirAdhelmar de Nointel, born about 1332, was once a real and stalwartpersonage, a younger brother to that Henri de Nointel, the fightingBishop of Mantes, whose unsavory part in the murder of Jacques vanArteveldt history has recorded at length; and it is with the exploits ofthis Adhelmar that the romance deals, not, it may be, withoutexaggeration._

_In any event, the following is, with certain compressions and omissionsthat have seemed desirable, the last episode of the_ Aventures. _The taleconcerns the children of Florian and Sylvie: and for it I may claim, atleast, the same merit that old Nicolas does at the very outset; since ashe veraciously declares--yet with a smack of pride:_

_Cette bonne ystoire n'est pas usee, Ni guere de lieux jadis trouvee, Ni ecrite par clercz ne fut encore._

Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice

Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice Chivalry

Chivalry Figures of Earth: A Comedy of Appearances

Figures of Earth: A Comedy of Appearances_preview.jpg) The Certain Hour (Dizain des Poëtes)

The Certain Hour (Dizain des Poëtes) Domnei: A Comedy of Woman-Worship

Domnei: A Comedy of Woman-Worship The Line of Love; Dizain des Mariages

The Line of Love; Dizain des Mariages The Line of Love. Dizain des Mariages

The Line of Love. Dizain des Mariages The Certain Hour. Dizain des Poëtes

The Certain Hour. Dizain des Poëtes The Jewel Merchants. A Comedy in One Act

The Jewel Merchants. A Comedy in One Act Gallantry. Dizain des Fetes Galantes

Gallantry. Dizain des Fetes Galantes The Cords of Vanity. A Comedy of Shirking

The Cords of Vanity. A Comedy of Shirking Domnei. A Comedy of Woman-Worship

Domnei. A Comedy of Woman-Worship Figures of Earth

Figures of Earth Jurgen. A Comedy of Justice

Jurgen. A Comedy of Justice Taboo. A Legend Retold from the Dirghic of Sævius Nicanor, with Prolegomena, Notes, and a Preliminary Memoir

Taboo. A Legend Retold from the Dirghic of Sævius Nicanor, with Prolegomena, Notes, and a Preliminary Memoir